Guest author Randal O’Toole has a degree in forestry from Oregon State University and has spent several decades studying forest policy. He is the author of six books, including Reforming the Forest Service, and author of The Perfect Firestorm: Bringing Forest Service Wildfire Costs under Control, a Cato Institute Policy Analysis.

Every summer, smoke from western fires drifting across the landscape is followed by repeated litanies from various interest groups. “If only we had more money to suppress fires,” says the Forest Service. “If only we were allowed to manage the forests” by cutting timber, says the timber industry. “If only people would stop driving so we could prevent global climate change,” say environmentalists.

In reality, wildfires in the West aren’t evidence of a lack of funds, forest mismanagement, or climate change. They happen because the West is a fire plain, and, just as a flood plain floods, a fire plain is going to burn. For as long as we’ve kept records, about one-half to one percent of the West burns each year, and nothing we can do is going to stop it.

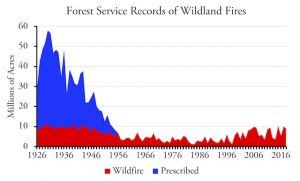

You may have seen a chart showing far more acres burned each year in the 1930s than in recent decades, which is often cited as evidence that global warming isn’t happening. In fact, it is evidence that the Forest Service was dishonest in its fire reporting.

This chart (to the left) shows how many acres were reported as burned each year since 1925 and my estimate of how many of those acres were prescribed burns and how many were truly wildfires. The best available data indicate that a few more acres burned in wildfires in the 1930s than in more recent years, but the difference isn’t great enough to prove anything about climate change. (The source of these data is Forest Service records at Oregon State University.)

In 1908, Congress gave the Forest Service a literal blank check for suppressing fires, but no money for prescribed burning. The Forest Service decided that prescribed burning was bad and it spitefully counted all prescribed fires conducted by private landowners as wildfires. This policy faded away in the 1950s, which is why the acres reported burned tapered off in that decade.

You may also have heard that many western states have suffered their largest fires in recorded history in recent years, which is often cited as evidence that climate change is the real problem. In fact, fires have not gotten more severe in recent years; instead, large fires are evidence of a change in firefighting strategies.

Before 1994, the Forest Service and other agencies directly attacked fires by putting firefighters on the fire front to stop fires from growing. In 1994, 14 firefighters who were directly attacking a fire in Colorado were overwhelmed and died. The chief of the Forest Service, Jack Thomas, ordered the agency to change strategies to protect firefighter lives.

Today, the more common practice is to have firefighters create fire lines well back of the fire front and do large backburns. One result is that fires burn far more acres but a third or more of those acres were lit by the firefighters. Another result, sadly, is that more, not fewer, firefighters are killed each year, but they are killed in ones and twos in aircraft crashes, auto accidents, and similar causes rather than groups of a dozen or more being burned over.

Another story is that we must regularly thin or used prescribed fires in forests to protect them from catastrophic wildfires. That’s true for southern pine forests, which grow so fast that they can become very fire-prone in just a few years. It is far less true for western forests, because fire suppression does not make most of them fire-prone. Even the ones that do become fire-prone due to suppressing fires require a lot more years of suppression for them to become a fire hazard. A 2001 Forest Service report found that less than 15 percent of western forests are in serious fire danger due to historic fire suppression.

More people than ever (including me) live in western fire plains, and each year we hear about evacuations and homes burning down. Forest Service research has shown that, to protect homes and other structures, it is both necessary and sufficient to treat the land immediately around the structures and the structures themselves to reduce flammability.

This means roofs and eaves must be non-flammable; no firewood or other flammables should be stacked against the buildings; and 100 to 200 feet around each structure must be landscaped to minimize fire: a grassy lawn is fine; a big thicket of pine trees is not. This is known as defensible space, and a truly defensible home and yard can survive the worst fires, whereas one that isn’t defensible is vulnerable to burning down no matter what adjacent landowners do with their land.

If you live in a fire plain, it is up to you to keep your home defensible as you can’t rely on firefighters to keep fires from reaching you. This means the Forest Service’s real problem isn’t a shortage of funds but having too much money and spending that money in all the wrong ways, such as expensive aerial tankers that, the agency’s own studies show, accomplish very little.

If you live in a city near a fire plain, such as Santa Rosa, California, then zoning codes that prohibit low-density development at the urban fringe are asking for trouble. If a fire reaches the edge of your city, and all the houses are ten to twenty feet apart, then when one house catches fire they will all catch fire. It is safer to surround the city with a broad zone of homes on one-half to one-acre lots that, if they are made defensible, will act as a fire break for the rest of the city.

We in the West live in a fire plain. It is going to burn. Our goal should not be to prevent the unpreventable but to adapt to it. That means making our homes defensible, maintaining safe evacuation corridors, and strictly limiting firefighting budgets so that agencies won’t waste money and firefighter lives on strategies and tactics that are not cost-effective.

Fire image is by Randal O’Toole. He describes it: “The fires that swept through western Oregon last fall burned forests that were not susceptible to becoming more fire-prone due to years of suppression; they were simply fire plains that will burn when conditions are right (in this case, hot weather and thunderstorms followed by strong winds). The only way to protect homes and communities from such fires is to make them defensible, as this one (where I live) is.”

Privatization of the forests wouldn’t reduce forest fires?

Walter Block,

Privatization of the forests will not reduce fires. The fires that burned in Oregon last Labor Day included tens of thousands of acres of private forests. Young plantations are especially susceptible to fire because they include branches to the ground, thus providing a “ladder” for fire to climb.

I find somewhat confusing the part where fire suppression seems to include measures such as prescribed burns and thinning. “Another story is that we must regularly thin or used prescribed fires in forests to protect them from catastrophic wildfires. That’s true for southern pine forests, which grow so fast that they can become very fire-prone in just a few years. It is far less true for western forests, because fire suppression does not make most of them fire-prone. ”

Reductio ad absurdum: Are we going to get big wildfires on clear cut lands? More reasonable: isn’t a well thinned forest much less fire prone than the public lands (and some conservancy lands) where hundreds of trees grow per acre?

Prescribed burns: I recall some demonstration forest work in northern California where a fierce wildfire stopped at a thinned and prescribed burn area.

Randal O’Toole’s careful work, whether on transportation or forestry, always provides well reasoned and documented critiques of conventional wisdom and fashionable policies.

Fire suppression is different from prescribed fire. There are some forest types where prescribed fire and thinning can reduce fire hazards. These include most pine forests in the South and ponderosa pine forests in the West.

But Douglas-fir, lodgepole pine, spruce, hemlock, and true fir forests in the West do not benefit from such treatments. These forests will burn if the conditions are right no matter what was done to them in advance. Clearcuts can actually increase fire hazards because the small branches and twigs that are likely to burn are moved from way up in the air to the ground.

Even in ponderosa pine forests, thinnings or burnings won’t be sufficient to protect nearby houses because fire brands can travel for miles. A few years ago a fire near Lake Tahoe burned hundreds of homes. Prior to the fire, the Forest Service had done prescribed burnings and thinnings on thousands of acres around the area, but the fire managed to cross the treated areas and reach the homes anyway.

These definitions (from Randal O’Toole) might be helpful: “Fire activity breaks down into fuel treatment, presuppression, and suppression. Treatment is thinning or burning. Presuppression is getting firefighters and equipment ready. Suppression is fighting the fires.”